My current research addresses two broad sets of questions: Cultural and Intellectual Inequality and Transnational Social Protection.

Cultural and Intellectual Inequality

I take up these issues through my current book project, Move Over Mona Lisa. Reimagining What We Read, Look at, and Learn and through a new project on Decolonizing Decoloniality.

Move Over Mona Lisa. Reimagining What We Read, Look at, and Learn.

We hear calls to globalize, internationalize, decolonize, and diversify cultural and academic institutions from many parts of the world. If everyone agrees that big changes are needed, why is change so slow? The answer is the inequality pipeline—a set of gates that aspiring artists, writers, and thinkers must pass through for their work to circulate globally. The pipeline begins when a toddler in the US or Europe is surrounded by art supplies while a toddler on the other side of the world is left empty-handed. It continues when a work by a theorist writing in a European language gets translated and travels widely while her peer writing in Arabic or Hindi is read only by people back home. And it extends through cultural and academic institutions to what gets taught in university classrooms and textbooks.

My book tells the story of how artists and writers from Argentina, Lebanon, and South Korea negotiate their way through the nodes of the pipeline and what enables some to travel easily while blocking others at every step of the way. I focus on how exclusions at the sites where art and literature are produced translate into additional exclusions in the classroom and in the textbook.

Decolonizing Decoloniality

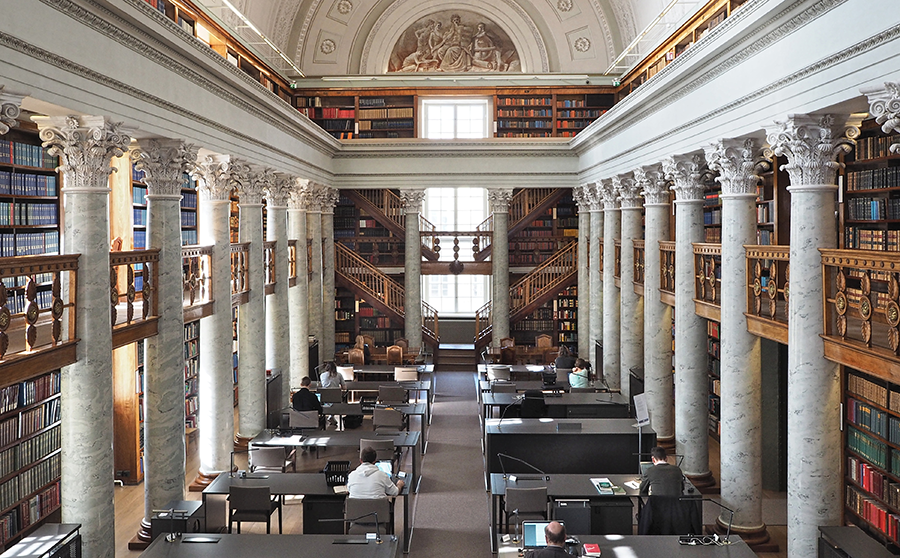

When people call for decolonizing the world’s universities, libraries, and museums, what do they actually mean? Who participates, what are they fighting for, and whose interests are served? What becomes clear once we start asking these questions is that these discussions evolve very differently in different parts of the world. Thus, the need to “decolonize” decoloniality and to ask empirically what scholars, teachers, and activists are actually trying to accomplish.

The Global (De)Centre (GDC) has begun a series of conversations with colleagues in Mexico, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Angola and Mozambique that take a grounded look at if and how these conversations evolve, what terms are used, and what their goals are. In addition, I have begun field work in Mexico in collaboration with Prof. Federico Besserrer, of the Cultural Anthropology Department at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UAM) and Dahil Melgar, Senior Curator at the National Museum of the Cultures of the World. We are researching decolonizing and decentering efforts in Mexican universities (including those aimed at indigenous communities), archives, and museums.

Transnational Social Protection: Changing Social Welfare in a World on the Move

In 2022, there were 110 million refugees around the world. In addition, in 2020, there were 281 million people living “voluntarily” outside their countries of origin. These figures don’t include the large numbers of people who move internally, temporarily, or who circulate regularly to work, study, or retire, for short or lengthy stays, without the intention or ability to settle permanently.

In this world on the move, there are increasing numbers of long-term residents without membership who live for extended periods in a host country without full rights or representation. There are also more and more long-term members without residence who live outside the countries where they are citizens but continue to participate in the economic and political lives of their homelands. There are professional migrants who carry two passports and know how to exercise their rights and raise their voices in multiple settings and there are many more poor, low-skilled, and undocumented migrants who are marginalized in both their home and host countries.

This picture raises fundamental questions—which institutions in which countries are responsible for protecting the rights of all these people and where do they fulfill the responsibilities of citizenship? Our traditional narratives about social welfare are that it is something provided by states to their citizens in a single place. But clearly this is out of sync with today’s reality. What’s more, in many parts of the world, the state is dramatically cutting back on or getting out of the social welfare business. Other states were never able to provide what they promised to begin with. In response, a new social welfare regime is emerging that sometimes complements, supplements, or substitutes for social welfare regimes as we know them. Migrants and their families unevenly and unequally piece together resource environments across borders from multiple sources, including the state, market, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and their social networks. Local, subnational (i.e., states and provinces), national, and supranational actors (i.e., regional and international governance bodies) are all potential providers of some level of care. Transnational Social Protection is not a cure for inequality. It redistributes rather than eliminates it.

My book,Transnational Social Protection: Social Welfare Across National Borders (co-authored with Erica Dobbs, Ken Sun, and Ruxandra Paul) was published by Oxford University Press in 2023. Our research continues as we test ways to adapt our framework and concepts in Latin America and Asia.